/ project

Click the + symbol to expand each section to learn more about this project.

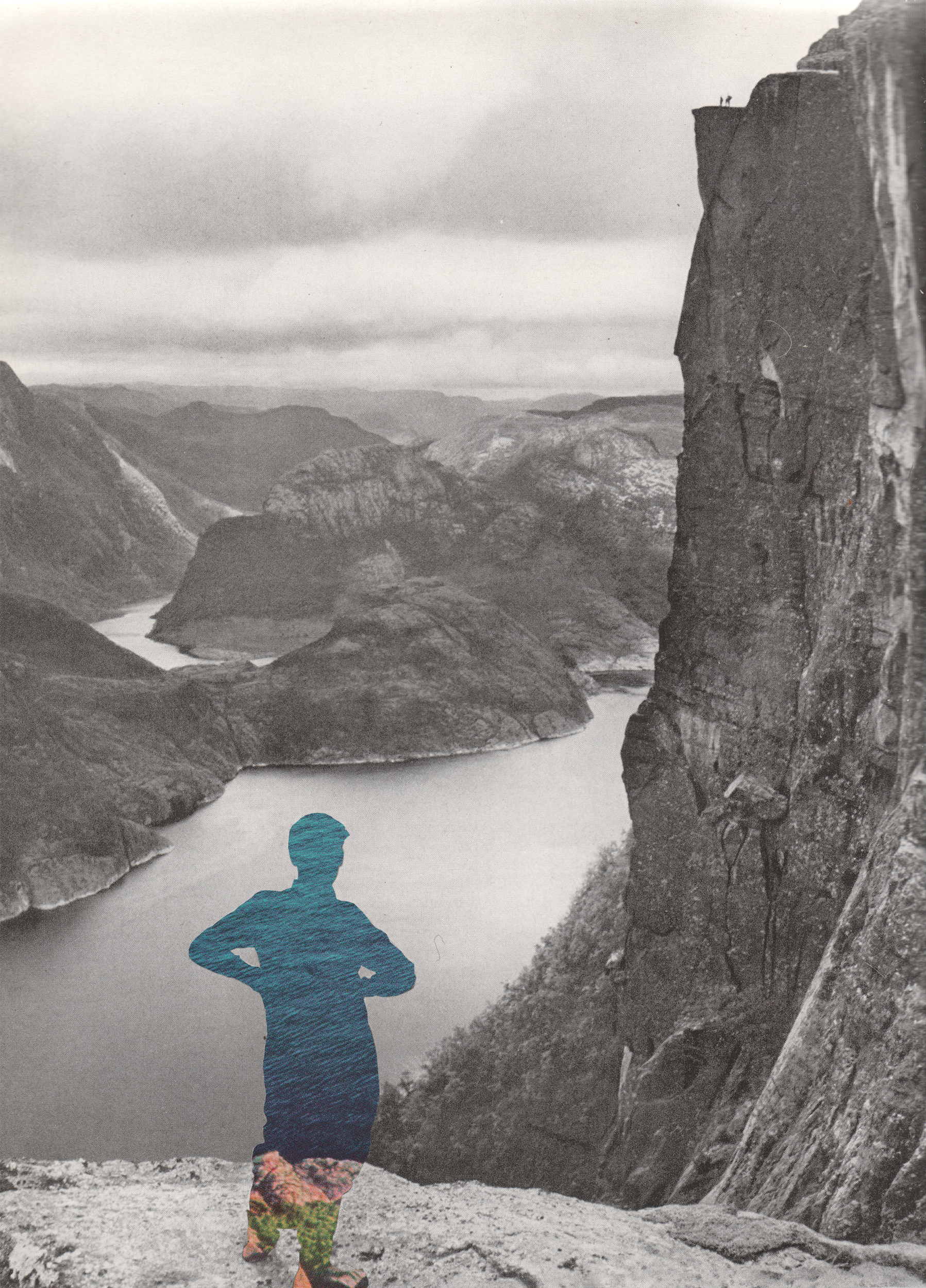

The multifaceted dimensions of this project endeavor to shift the narrative away from historically dominant male perspectives that have glorified human conquest over nature while overlooking and silencing the contributions of women and marginalized communities.

“Conglomerate Knowledges – Remedies For Species Loneliness,” advocates for a paradigm shift towards a more nurturing and interconnected relationship with the more-than-human world.

By challenging the current systems that emphasize the notion of humans as “masters over nature”, the project seeks to disrupt and decentralize our human perspective and offers methods towards fostering profound respect, reverence and connection for our more-than-human kin. It aims to portray nature not as a commodity to be exploited, but as a network of interconnected beings, existing in kinship, reciprocity, community, and experienced with a sense of awe.

“Remedies For Species Loneliness” is an effort to re|kindle our deep ancestral ties to the more-than-human world as a means of cultivating pathways of care towards our planet and the complex communities that encompass it.

Central to the project is an exploration of “species loneliness” and its impact on human-to-more-than-human relationships, as well as its role in exacerbating planetary destruction and the erosion of community bonds. Through various artistic mediums such as visual art, interviews, audiovisual projects, and written publications, the project endeavors to elucidate the consequences of species loneliness and propose solutions rooted in ecofeminist principles.

The project also prompts critical questions about the historical dominance of male voices in scientific inquiry and exploration – and academia as the guardian of knowledge. It asks how the inclusion of diverse voices, particularly those of women and marginalized communities, might have altered our understanding of nature and alerted us to the dangers of exploitation. Moreover, it reflects on whether a more inclusive approach could have preserved our intimate connection with the more-than-human world while still advancing technological progress.

In its current phase, the project primarily manifests visually, with plans to expand into various other mediums including written volumes, audiovisual productions, a pocket-sized “survival guide,” and a podcast featuring interviews with diverse perspectives and offering various methods on reconnecting with the natural world. This deliberate approach to art-making emphasizes slow, intentional engagement and acknowledges that the project will continue to evolve over time. Viewers are encouraged to stay engaged with the ongoing development and unfolding of the project.

For the sake of full transparency, I would like to preface this journey with the fact that I am not a scientist or scholar. The course of my life did not evolve in that way, though looking back, in some ways I wish that it had. But over the years, I have found that there are many means and methods of knowing and acquiring information and wisdom. Some pathways are more obvious than others, some are easier to access, and some require time and patience and an open mind. Much of the words you will read here, the images that you will see, sounds you will hear – are my observations and/or opinions that are the result of my own personal research and living and being in/with the world.

Women like myself along with knowledge bearers and sharers in BIPOC communities, and those in the working class who had a thirst for knowledge, have historically been relegated to the margins, their contributions to science and academia silenced, stolen or disregarded all together.

Take for example Mary Anning. Mary, who was born into a poor family in Lyme Regis in the United Kingdom in May of 1799, with limited formal education would eventually become known around the world for the discoveries she made in the Jurassic marine fossil beds within the cliffs along the English Channel. However, during her lifetime, even though she knew more about fossils and geology than many of her wealthy male counterparts to whom she sold her discoveries, because she was a woman, was unable to join the Geological Society of London and often she was not credited for her scientific contributions.[1]

Or take Eunice Foote, an American scientist who, in the 1850’s discovered the Greenhouse Effect, whose work was often credited to British scientist John Tyndall.

Or African American scientist Alice Ball, who in 1916 discovered a breakthrough treatment for Leprosy. Passing away shortly after her discovery due to a lab accident, the head of her department Arthur Dean continued her work and published the findings under his own name.[2]

Outside of the hard sciences and academia, lie other forms of knowledge and knowing the intricacies of the natural world that ride beyond the boundaries of scientific methodologies. Indigenous ways of kinship and reciprocity with the earth, such as healing with plants, sustainable agricultural practices and land management and fair governance systems were considered primitive. However, the basis of American democracy was modeled after the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace. Now, after the initial and subsequently continued affects of colonization and genocide of Indigenous peoples around the world, are we waking up to the importance of Indigenous knowledges for sustainability and healing the planet as we navigate through the climate crisis.

You can not have marginalization without the practice of domination. We humans, despite our capacities for compassion, learning, innovation and imagination, have a bad habit of “Othering”. On a human to human level, Othering can be defined as a phenomenon in which some individuals or groups are defined and labeled as not fitting in within the norms of a social group. Othering is a way of negating another person’s individual humanity and, consequently, those that have been “othered” are seen as less worthy of dignity and respect. It is an “us vs. them” way of thinking about human connections and relationships. [3] The strengths of Othering lie in its analytical capacity to capture knowledge structures, power relations, and categorization processes in their interconnectedness and to identify their effects on different levels. Furthermore, Othering offers the potential to make power relations accessible and visible in their intersectional manifestations. Othering often uses the power within relationships for domination and subordination. [4]. Othering is cemented in the annals of history throughout the world, culture and society. Here in the United States, one does not have to look back far to see how this phenomenon plays out. Racism towards BIPOC communities, our treatment of migrants and immigrants and those who harbor different religious and faith beliefs outside of Christianity, is ongoing. Colonization of Indigenous lands for the expansion of industry and the disposal of industrial waste, and the erasure of Indigenous culture and history is not a thing of the past that you read in history books, it is happening as I write these words.

This concept of Othering, also applies to human-to-more-than-human relationships as well. Man and the Environment are considered different, our more-than-human kin are considered as the “other” from “people”. The process of othering leads one to assume a position of superiority and domination over the other. [5] It could be said that the philosophical view of Anthropocentrism is derived from this mindset and way of being with the world and why we find ourselves in the environmental mess we do today. It has histories dating back to the Bible and was perpetuated during the Age of Enlightenment. Indigenous scientist and award winning author Robin Wall Kimmerer eloquently reflects upon this in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, when considering the differences between the creation story of Skywoman, in comparison to the creations stories of Western traditions, stating “Look at the legacy of poor Eve’s exile from Eden: the land shows the bruises of an abusive relationship”. EcoFeminists such as Donna Harroway, Susan Griffin and Rachel Carson have argued that the anthropomorphic worldview that has carried us today, is in fact a male, or patriarchal, point of view and that to view nature as inferior to humanity is analogous to viewing other people (women, colonial subjects, non-white populations) as inferior to white Western men and, as with nature, provides legitimacy for exploitation. [6]

It is hard for me to ignore the threads that connect the historical domination of man over nature, and the oppression of women and marginalized communities to our current environmental crises. I can’t help but be critical about the historical dominance of male voices in academia, scientific inquiry and exploration that have shaped the way we view and relate to the natural world. I often wonder how the inclusion of diverse voices might have altered our understanding of nature and alerted us to the dangers of exploitation and I reflect on whether a more inclusive approach could have preserved our intimate connection with the more-than-human world while still advancing societal and technological progress.

~

Change can be hard. As a society, we have come to know and settle into comforts that resonate with the pace of modern life. Other aspects settle in more like a bad habit, hard to get rid of because it is what we are so used to or we simply don’t want to, or know how to rock the boat. With this, we willingly or unwillingly, allowed the systems that perpetuate individualism, consumerism and exploitation of people and planet to write the current narrative of our time here on Earth.

I understand that it is hard to simply find time for ourselves, let alone making time for being in and with nature. It is hard to consider giving up or changing certain comforts we have come to depend on, when for many of us we already sacrifice so much to simply just survive and get through each day. I understand how many don’t have the resources, support or means to make significant changes in their own life or community, let alone along societal lines.

But change can be easy in small increments and simple gestures. You can start in your own back yard, the park you pass on your way from work after a long day, or on a weekend where you have a moment to breathe after a long week, if only for some fleeting moments. It can start by putting down your phone, using the time you would in front of a screen to spend just a few moments outside listening to birdsong and learning the name of the bird to whom the voice belongs, taking a walk in the rain and paying attention to the sensation on your skin, or picking up an interesting looking pebble on the street and running your fingers over its textures and boundaries – contemplating what it has experienced with it’s time on the surface.

I am a firm believer in that if we want something bad enough, we will find the pathways and support to reach those goals. I believe that if we love something hard enough, we will do everything we can to try and protect it, and ultimately, I believe that the inherent good, compassion and capacity to love we encompass within us can be harnessed to change the course we are currently on.

In the short time our species has been present on Earth, we have found ways to alter the planet and our society in ways that are profound enough to be recorded in the geologic record, and noted in the annals of human history. If we have the ability to do such damage to our planet, to other human beings and to more-than-human beings, we also have the ability to break our habits, dismantle our systems and move forward in reciprocity and respect for each other and nature. Small acts can inspire larger movements, movements can inspire r\evolutions, and r\evolutions open the door and make space for systemic change. Please note that by r\evolutions I do not mean or encourage taking up arms and starting an insurrection or war – war and conflict is already part of the problem – by r\evolution I simply refer to the collective imagining of a widespread community that want something better, demanding that the status quo needs to shift, that practices of domination and exploitation need to end, and taking positive and productive ways of acting together as a collective to make that happen. It is r\evolution with an emphasis on evolution. As a species, we need to learn to evolve a closer kinship with nature or else she will eventually find her own pathways towards restoring planetary balance and ultimately, we may not be part of that equation.

We humans, in some way, shape or form – all experience the effects of species loneliness, stemming from our disconnection with nature. Whether we realize it or not, we long for a sense of community, where we feel supported and uplifted. To find proof of this, all you need to do is look to social media. However, these technologies that tout connection, have made us more disconnected than ever. To quote author and environmentalist Terry Tempest Williams, “To be whole. To be complete. Wildness reminds us what it means to be human, what we are connected to rather than what we are separate from.” These words could not ring more true. To reconnect to nature, is to reconnect to ourselves, community and the very essence and elements of what makes us human. We humans can benefit individually and collectively by making time to find and nurture ways to reconnect to our more-than-human kin, and in reciprocation, they will continue to nurture us and our existence.

In conclusion, I am simply just a woman and mother. I am the great-granddaughter of Ukrainian/Lemko/Polish immigrants who were forced off their ancestral lands by oppressive regimes, and who ended up seeking a better life on unknown soil. I recognized that I am disconnected from the place of my ancestors and the more-than-human kin that they would have known and respected. I fumble through this feeling searching for a sense of place where I currently reside, and look for threads that weave and interconnect old ways of knowing, with new ways of being. I am just an artist, advocate, citizen scientist, writer and life long learner – with an insatiable passion for nature and desire to understand the more-than-human beings, processes, and timelines that I share this planet with.

With such deep reverence – comes the urge of responsibility to care for, respect and protect these kin – much like one does their family. This project is one of the ways I hope to do that, however small of a gesture it may be in the scheme of things. It is my goal to offer collected/collective/ marginalized and more-than-human knowledge(s), scientific contributions and potential solutions/remedies for “species loneliness” in an effort to shift our modern day practices and perspectives away from Anthropocentrism and towards a more just, connected and balanced way of living in and with the world. I hope that the information here can inspire others to lean into and embrace different means of listening, learning, attuning, making, consuming, interacting and ultimately re/connecting with our more-than-human world in kinship and reciprocity.

I hope this project and the elements that encompass it can serve as a gentle guide, leading you back to your own personal connection with nature and our more-than-human kin, and help to inspire pathways of care for our planet. As my dear friend Kawenniiosta Jock, Kanien’kehá:ka (People of the Flint) Orenhrekó:wa (Wolf Clan) mother, activist and land ReMaitriator says – “when we heal the land, we heal ourselves”.

Now is the time to begin ….

species loneliness : /spēSHēz,ˈspēsēz ˈlōnlēnəs/ (noun)

species loneliness : /spēSHēz,ˈspēsēz ˈlōnlēnəs/ (noun)

Species loneliness can be defined as a profound sense of disconnection and isolation experienced by humans amidst their estrangement from more-than-human kin, as a result of our dominant anthropocentric worldviews, hyper-consumerism, and deepening dependencies on “social” technologies.

This loneliness stems from our (human) estrangement from the intricate web of life, where more-than-human beings are often relegated to mere resources or objects devoid of vitality. It unveils the consequences of patriarchal structures that devalue interconnectedness and perpetuate the exploitation of nature.

The term was originally coined in 1993 by Author Michael Vincent McGinnis in an article in Environmental Ethics.

Indigenous scientist, bestselling author and winner of the John Burroughs Medal Award for Natural History Writing – Robin Wall Kimmerer‘s subsequent references in her publication Braiding Sweetgrass – deepen this concept, emphasizing the importance of reciprocity and kinship with all living beings, illuminating the necessity of rekindling our connection to the broader community of life for collective well-being.

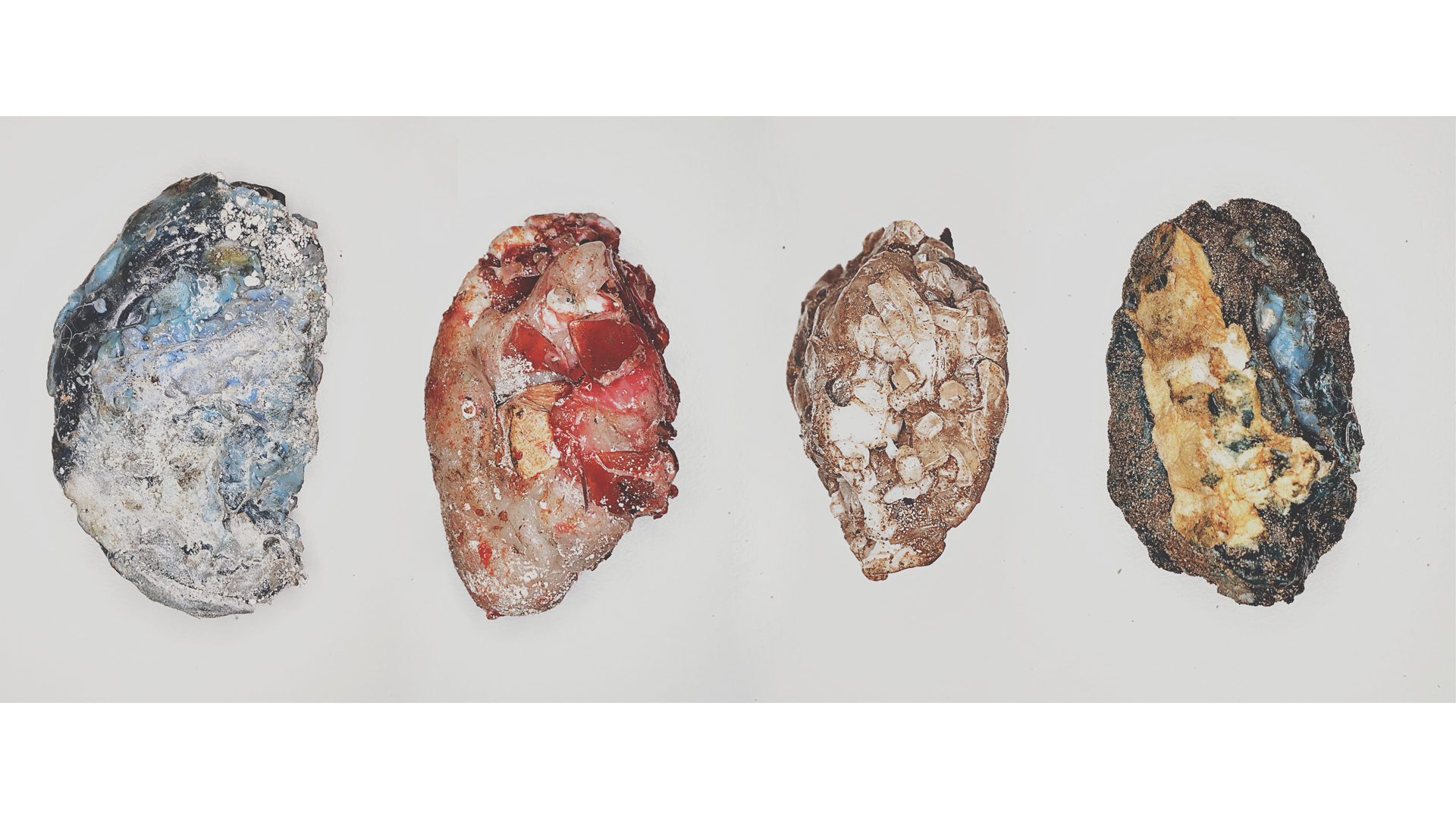

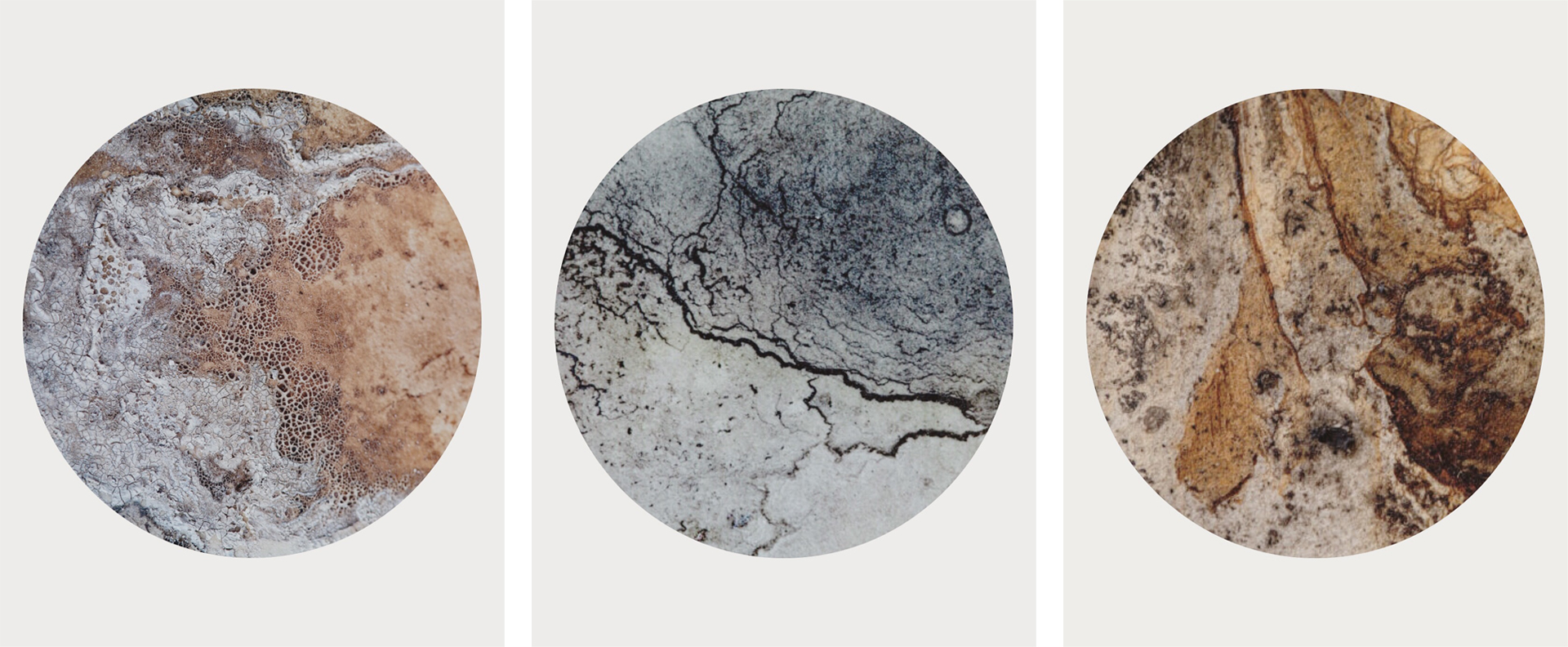

conglomerate: kənˈɡläməˌrāt/ 1. gather together into a compact mass.

The concept of/term Conglomerate Knowledge(s) represents the coming together of various forms of knowledge and knowing. This space is serves as a bond , holding space for these various forms together. From lessons learned directly from our more-than-human kin, Indigenous knowledges to scientific methods and art making, Conglomerate Knoweldges(s) hopes to serves as a mingling place for these forms to coalesce and inspire ways of re/connecting to our planet.

The concept of/term Conglomerate Knowledge(s) represents the coming together of various forms of knowledge and knowing. This space is serves as a bond , holding space for these various forms together. From lessons learned directly from our more-than-human kin, Indigenous knowledges to scientific methods and art making, Conglomerate Knoweldges(s) hopes to serves as a mingling place for these forms to coalesce and inspire ways of re/connecting to our planet.

CLICK [HERE] TO EXPLORE THE VARIOUS WAYS TO CONTRIBUTE + SUPPORT THIS PROJECT

/ VIDEO

TRANSFORMATIONS

/ SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS + SOUNDSCAPES

Enter the library for field recording and soundscapes recorded in collaboration with the more-than-human world. Listen to the languages of the planet – what do you hear them say? What do you understand? Also included are tips for making your own field recordings and soundscapes.

/ ART

/ BOOKS + PUBLICATIONS

Remedies For Species Loneliness - Pocket Survival Guide

A printable set of PDF survival guides for navigating the Anthropocene and species loneliness.

COMiNG SOON!

Recommended Readings + Research

Read more inspiring texts + research around the subjects of species loneliness, nature re|connection and the more-than-human world.

/ PODCAST + VIDEO SERIES

/ NEWS + MUSINGS

Elegy For Petric Kin

by SE Bachinger Long before we grasped for a hold upon terrestrial skin, Before the echos of human song reverberated, Fervent forces pulsed, a rhythmic memory, Their hands, not our

Conglomeration

Welcome to this project – it has been a long time in the making – a conglomeration of all of the facets of my work over the years; my passions, my independent research

/ CONTRIBUTIONS

CONGLOMERATE CONTRIBUTIONS : KNOWLEDGE

Search the knowledge repository for exercises, musings, thoughts and practices from contributors around the world. We hope that these contributions inspire you to unplug, cultivate mindfulness and offer avenues for re\connecting with the more-than-human world that we are all part of.

CONGLOMERATE CONTRIBUTIONS : SUPPORT + PROJECT REALIZATION

Though there is much we can do on an individual level to reframe our perspectives and put into practice frameworks of re\connection to our more-than-human world for the betterment of the planet – and all societies living upon and with it – it takes a collection and community to truly initiate societal change. Thank you to the supporters of this project – whether it be through financial contributions to materialize aspects of it in tangible ways, brining elements of practices shared here into your communities or classrooms, or simply sharing the work here through your channels and audience – each contribution is an act of reciprocity and a step closer towards collective shifts.

/ EVENTS + HAPPENINGS+ CALLS TO ACTION

PROJECT EVENTS

KIN + COMMUNITY EVENTS

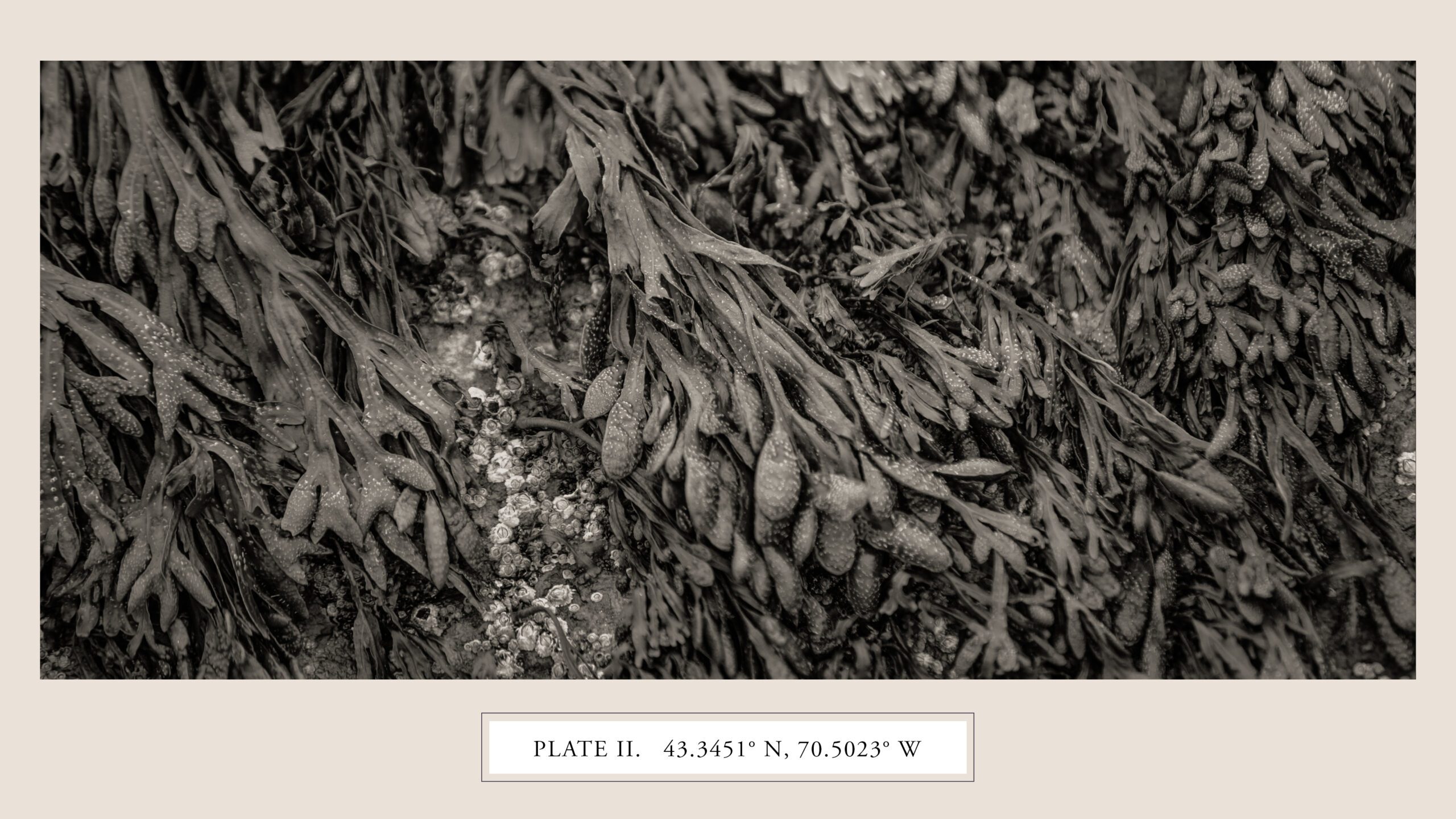

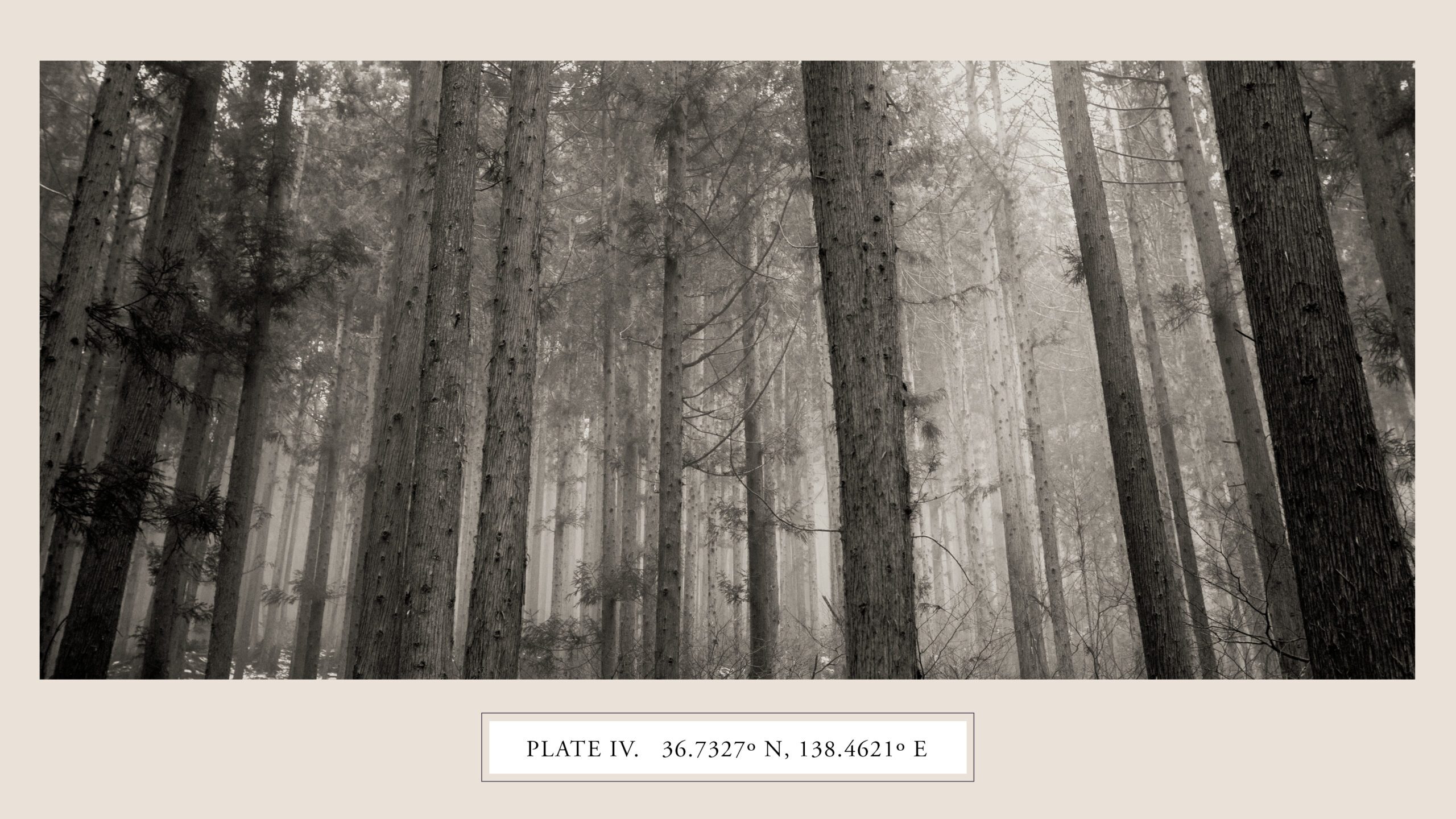

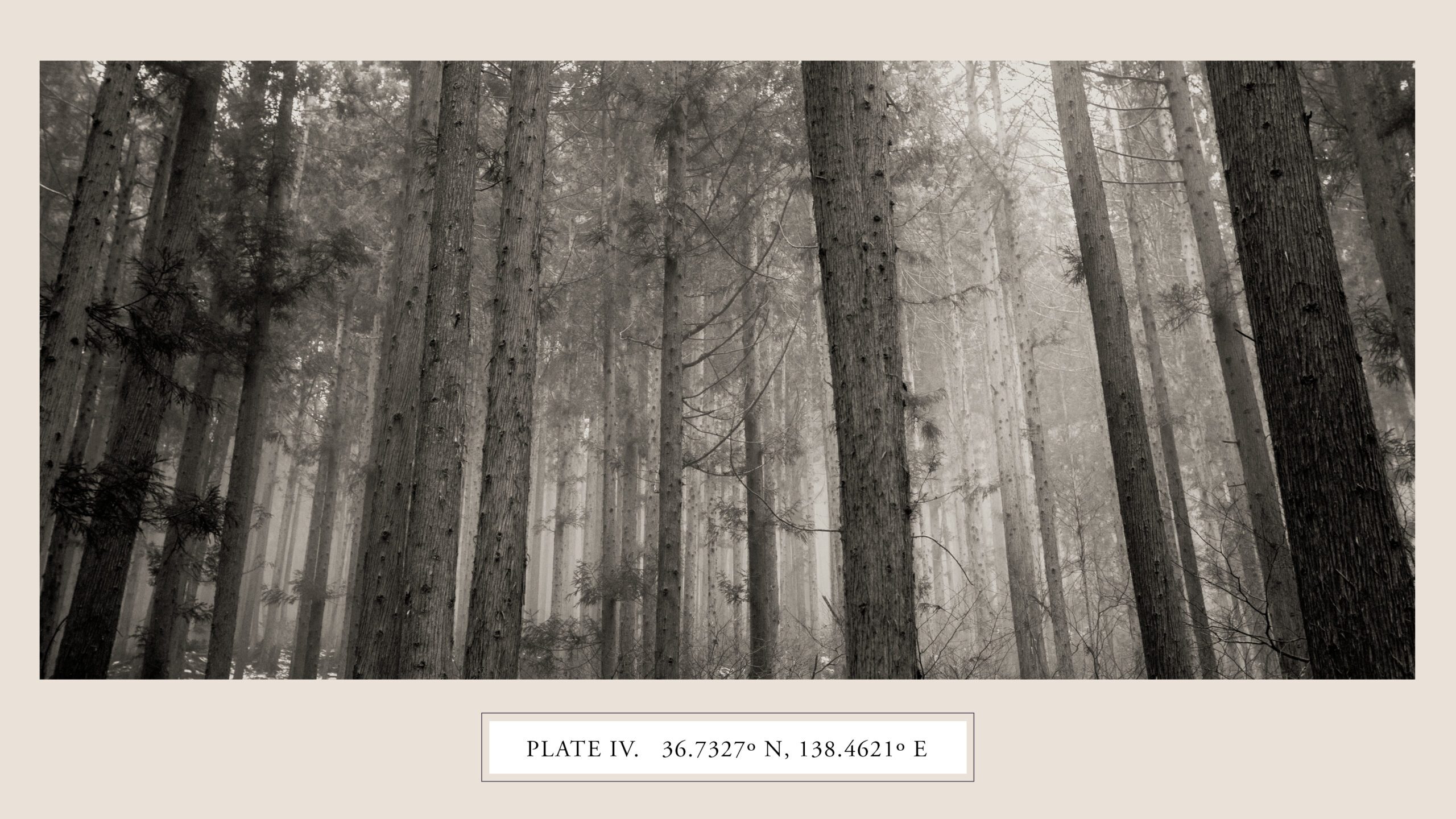

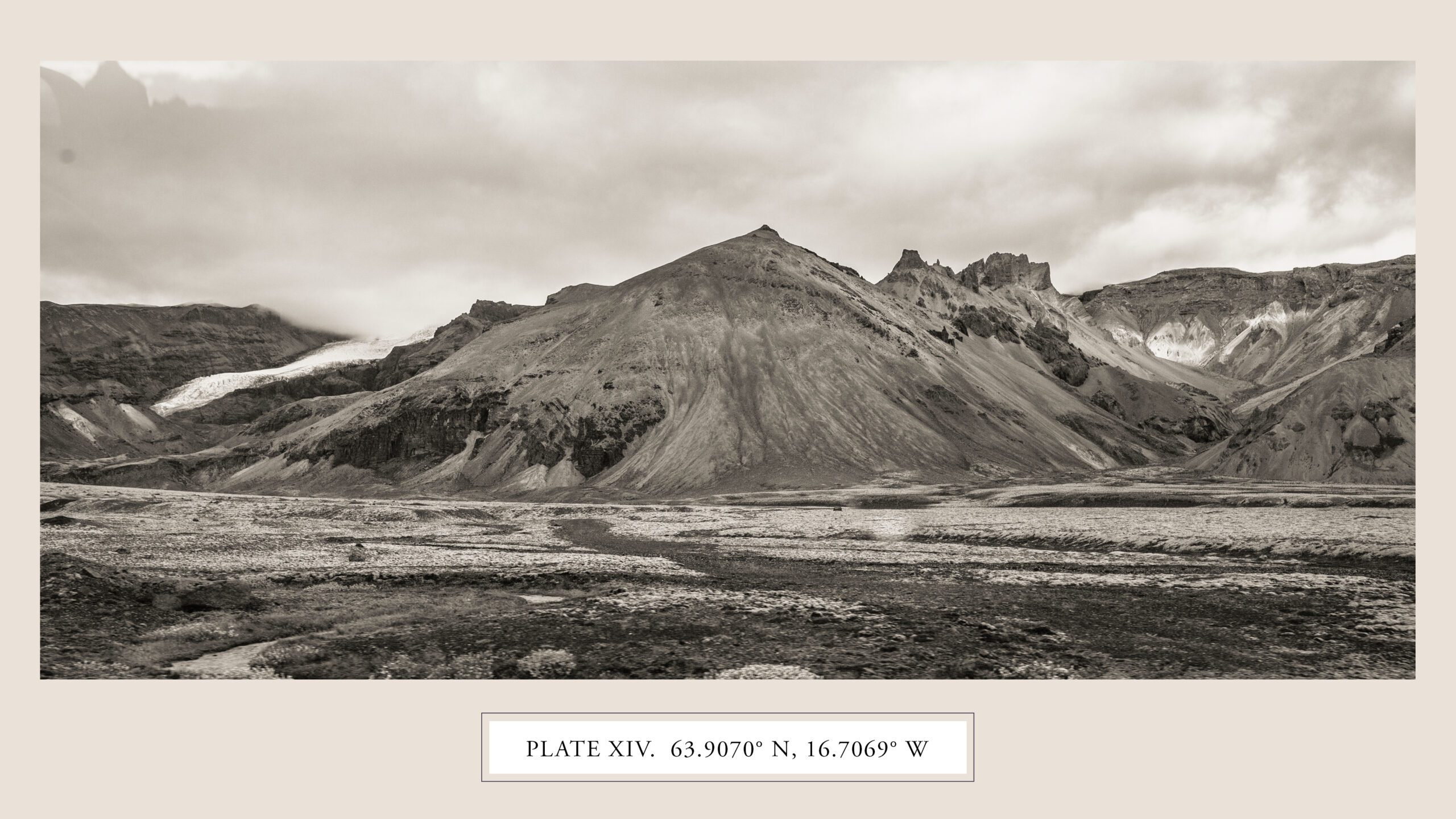

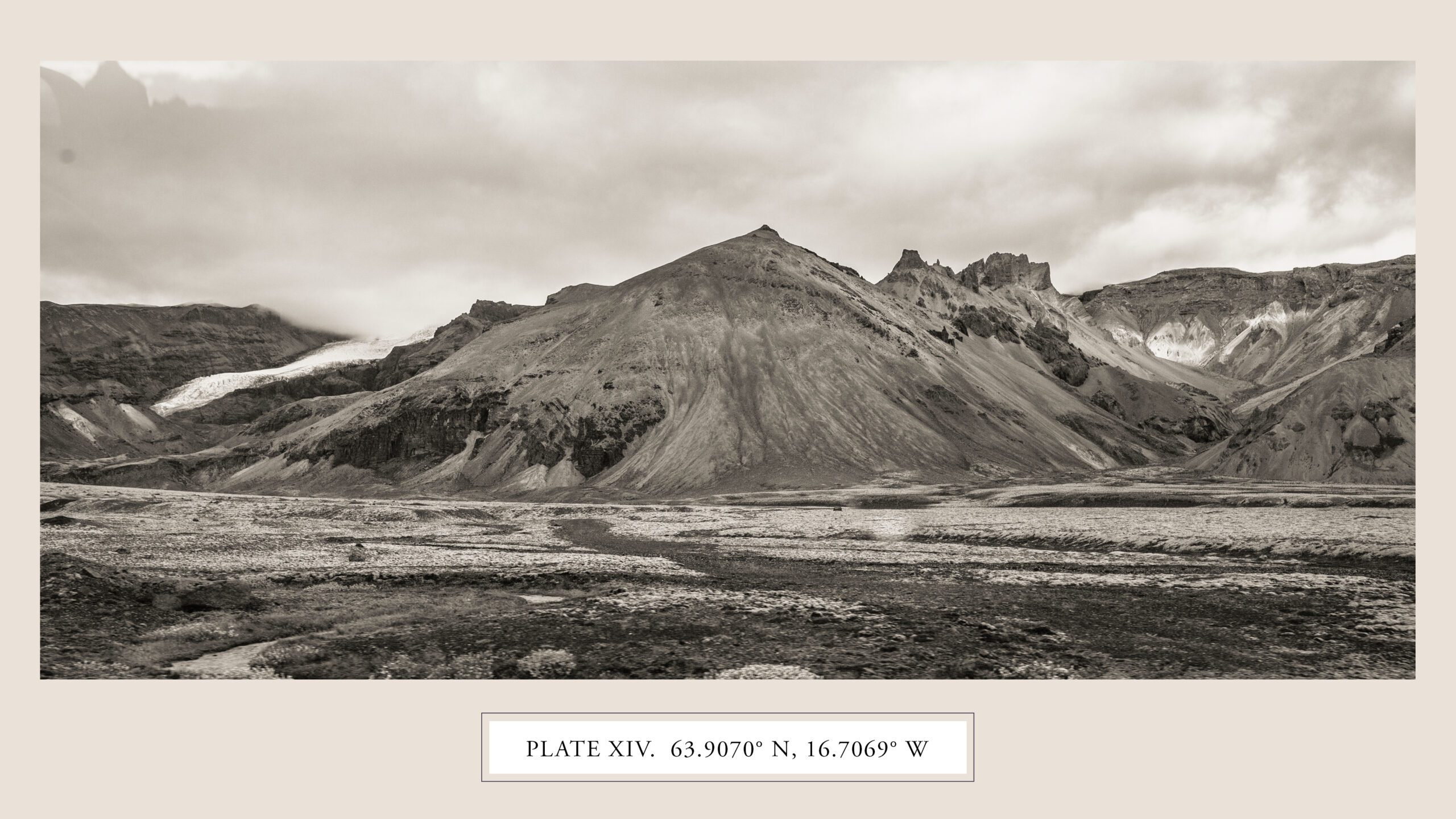

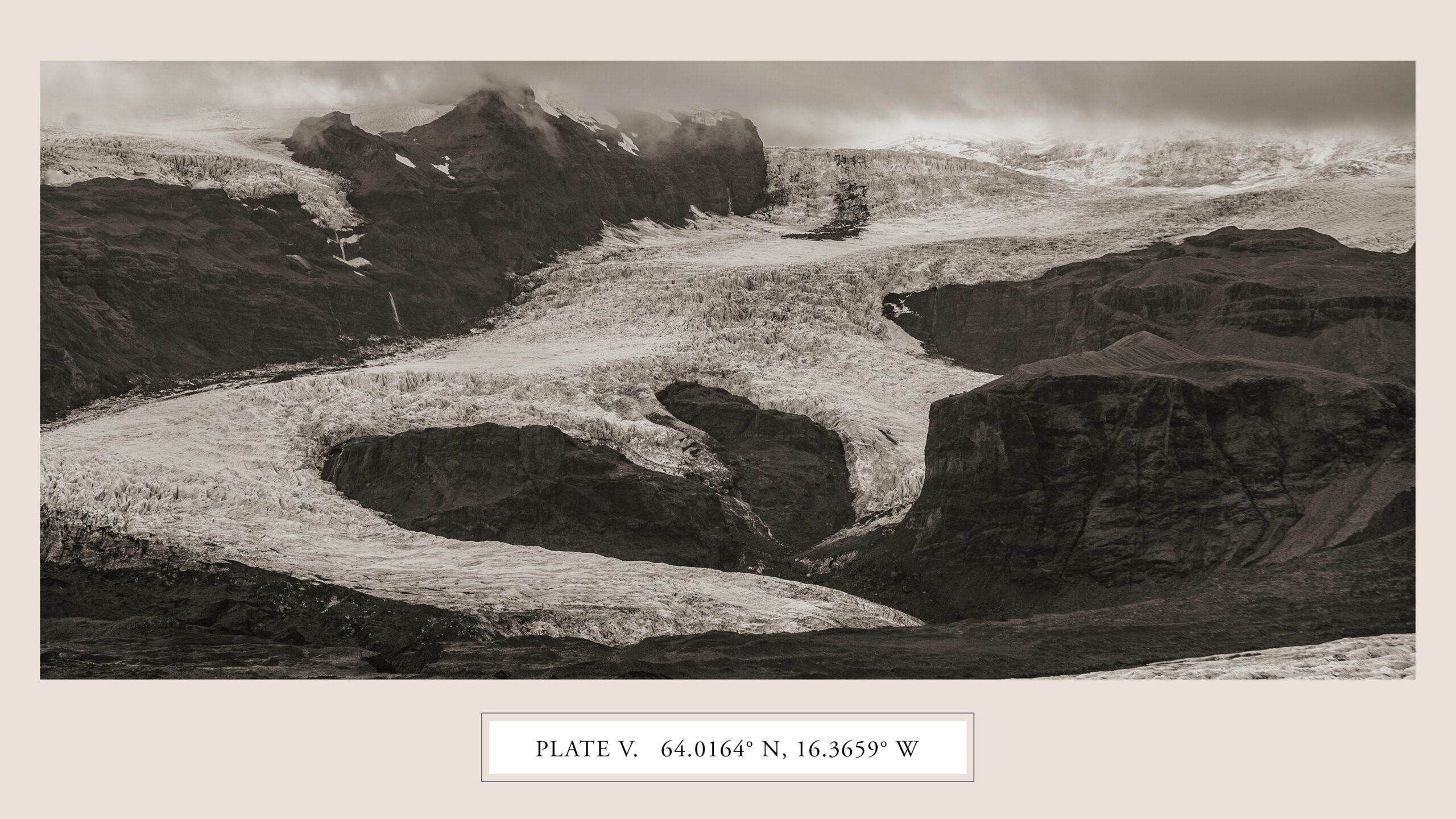

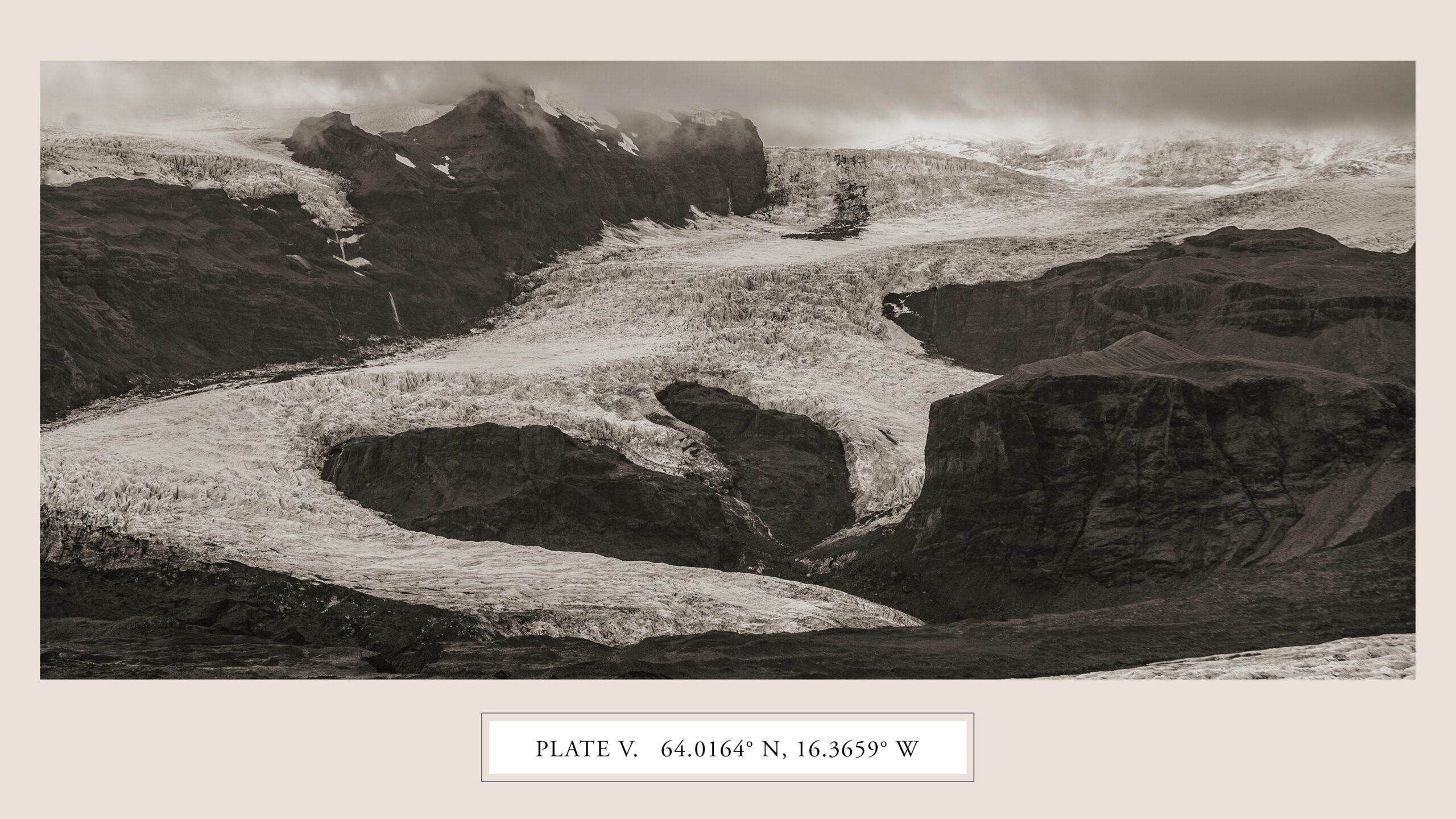

/ PRINTS + PATRONS

Limited edition, signed, numbered and dated Fine Art giclee prints are available for purchase directly from artist SE Bachinger. The monies raised from the sale of prints, one of kind art objects relating to this project, limited handmade artist books + Zines, and/or a subscription to Patreon go directly back to this project for research, public art practices and engagement, submissions to conferences to share this work, and the continued progress of this project in various forms such as printed publications and imagined manifestations yet to reveal themselves . If you are interested in purchasing a print to help out the project, please visit the shop to learn more.